What are the characteristics of urban space?

![]()

“Walking conditioned sight, and

sight conditioned walking,

till it seemed only the feet could see.”1

– Robert Smithson

till it seemed only the feet could see.”1

– Robert Smithson

What is the experience of an urban space?

“We are not simply observers of this spectacle, but are

ourselves a part of it, on the stage with the other participants. Most often, our perception of the city is not sustained,

but rather partial, fragmentary, mixed with other concerns. Nearly every sense is in operation, and the image is the

composite of them all.”[1]

– Kevin Lynch

This section of the paper will consider the characteristics of urban space both as I experienced it through my research and also as others have described or experienced it.

Our experience of an urban space is often attached very tightly to our sensorial contact with it. Closing our eyes, we can remember how a street smelled even if we find it hard to recall the image of it. "We can know a place subconsciously, through touch and remembered fragrances, unaided but the discriminating eye. While the eye takes in a lovely street scene and intelligence categorises it, our hand feels the iron of the school fence and stores subliminally its coolness and resistance in our memory.”[2]

My walks had shown that the actual lived experience of urban space is always that of being immersed in the space. The space entirely surrounds us, and this can make it difficult to perceive the space. One is never "in front of" any more than one is "in." In such close vision "no-line separates earth from sky, which are of the same substance, there is neither horizon or background nor perspective nor limit nor outline or for nor center; there is no intermediary distance, or all distance is intermediary."[3]

In my explorations of Klybeck I was conscious of perceiving completely, following the example of Maurice Merleau-Ponty, "My perceptions are {therefore} not a sum of visual, tactile and audible givens: I perceive in a total way with my whole being: I grasp a unique structure of the thing, which speaks to all my senses at once.”[4]

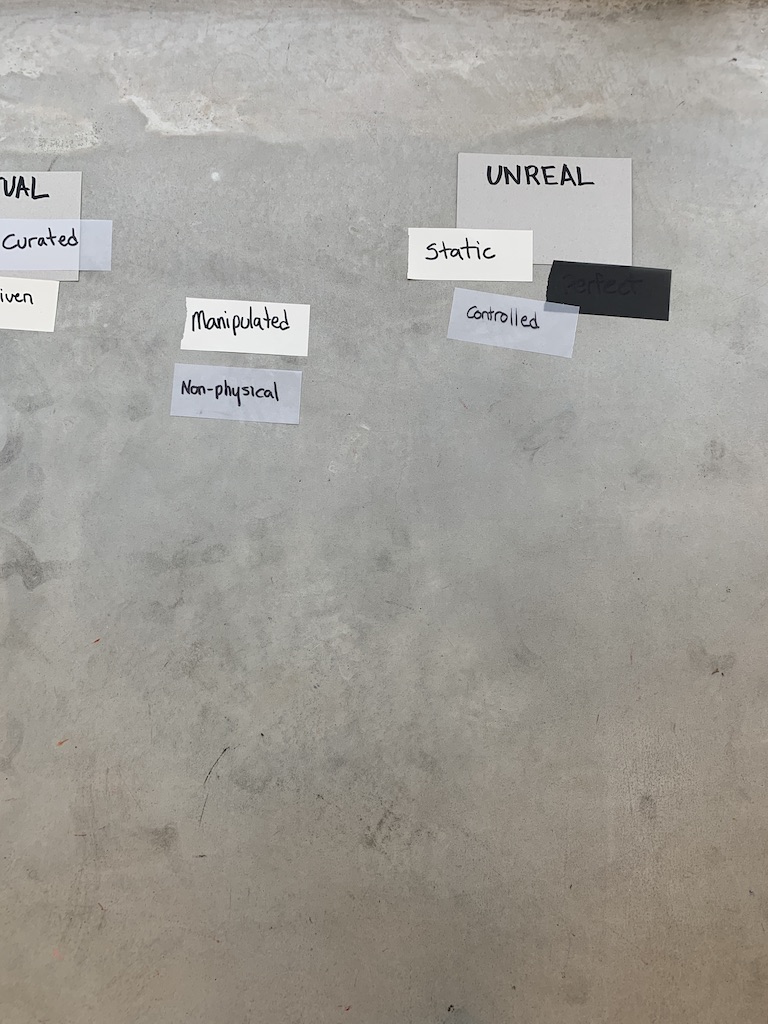

Moving forward practically, I began to consider the large amount of image material, notes, found items and audio/video recordings generated by my research walks. By carefully looking and analysing the material, alongside my narrations and memories of the space, I began to observe a series of characteristics that I found in common through each of my walks. I began to make categories of what I felt were the characteristics most representative of the experience of urban space, writing down keywords that described these experiences visible in the images and other research material.

Transferred to cards and arranged in different ways these keywords began to flow around my workspace, requiring me to walk and bend to change configurations. The physicality of this exercise was part of the process, mimicking in some ways the walking I did as research, viewing the keywords from different angles and in proximity to other words created new view-points. I was starting to make a map of the characteristics of the experience of urban space.

In the initial configuration, I settled on only three categories, real, virtual and unreal. By ‘real’ I meant images or sensations that were only possible in the actual lived space, ‘virtual’ referred to images only possible in the virtual world. The images in between the categories were visible in both categories. As can be seen above (fig.10), many of the keywords were placed somewhere between Real and Virtual.

My experience, though, had been more complex than this initial breakdown indicated. The experience of the space overlapped real and unreal without regard and was perceived as a unique mental event. The image material

and narrations I had gathered reflected bodily sensations and movement at a specific moment in time, as well as what I had chosen to focus my gaze on, and finally, a layering in the mind of my previous experiences, physical, virtual or imagined. Using Yi-Fu Tuan's statement: "Visual perception, touch, movement and thought combine to give us our characteristic sense of space.",[5] I created new categories and groupings to reflect these characteristics as well as a section for the virtually experienced space.

I moved these keywords within the new categories and further defined the experience of urban space into the following categories and subcategories as seen here:

This final grouping, seen above, created three sections with a series of subcategories under each heading, which I will use moving forward in my investigation of the experience of urban space. (fig.11)

TACTILITY, TIME AND MOVEMENT

Sound & Smell, Texture, Shadow, Quality of light, Repetition, Freedom of Gaze, Atmosphere

DETAILS, LAYERING AND MEMORY

Unexpected, Unplanned, Reflection, Memory, human presence & personalization

VIRTUAL AND UNREAL

Untethered, Gravity Free, Curated, Deceptive, Analytical, Open

The images, videos and narrations I had gathered and moved into these final categories represented my unique experience of the space. As Mâdâlina Diaconu describes it, "Urban space represents neither a neutral, nor an empty container, but evolves as a dynamic environment through its dwellers' bodily engagement, whose very sensory experience 'opens' and constitutes the space as atmosphere.”[6] This uniqueness of the individual's experience of urban space did not mean; however, that there were no points or commonalities with others' experiences as well, and this will be discussed further within each category.

[1] Lynch, 2005 p.2

[2] Tuan, 2001 p.411 (Here referencing Helen Hoover Santmyer in Ohio town, Ohio State University Press, Columbus Ohio 1962

[3] Moya Pellitero, A.M., 2007 p. 95 (here quoting Gilles Deleuze from Gilles Deleuze, A Thousand Plateaus: Capilatism and Schizophrenia (1987) in The Deleuze Reader (New York: Columbia University Press, 1993).

[4] Merleau-Ponty, 1964 p.50

[5] Tuan, 2001 p.390

[6] (Mădălina Diaconu, Heuberger, Mateus-Berr, & Vosicky, 2011) p.7