Tactility, Movement and Time

ATMOSPHERE | TEXTURE | FREEDOM OF GAZE |

RHYTHM |

REPETITION |

QUALITY OF LIGHT | SHADOW

“We behold, touch, listen and measure the world with our entire

bodily constitution and existence, and the experiential world is organised and articulated around the centre of the body.”[1]

– Juhani Pallasmaa

The primary observation that I made as I analyzed my research material was the importance of my body in seeing and understanding the space. This 'seeing' went beyond visual impressions and included many other sensations at once; touch, sound, smell, the heat of the sun, the cool feel of the wind on my skin as I turned a corner. This sensation of the space was all-encompassing. According to Ken-Ichi Sasaki, "The most profound knowledge of the city is a tactile one. But it excludes neither vision nor intelligence. Tactile knowledge requires merely that our body is involved."[2]

Atmosphere

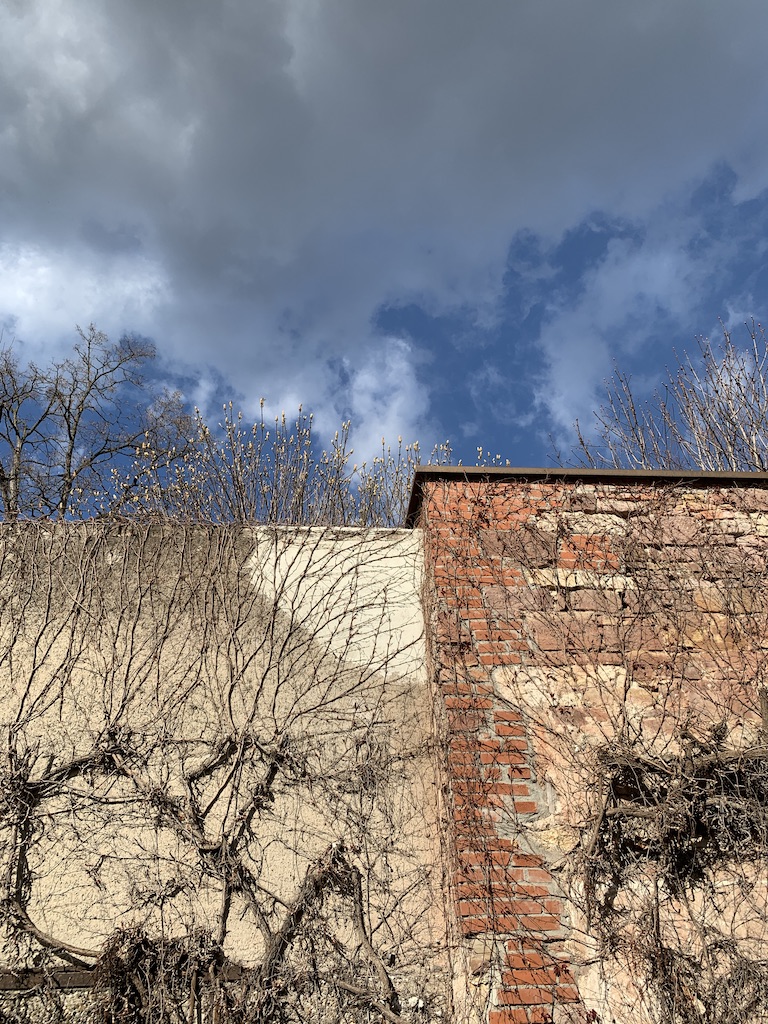

Tactile knowledge which engages all of our senses works to create 'atmosphere' or an overall feeling or mood from the many physical sensations, feelings and thoughts our body receives at once. This atmosphere is not something we can create without the sensorial experience. Juhani Pallasmaa stated; "We feel atmospheres immediately and without being conscious of the process"[3], or consider, even more poetically, Anton Ehrenzeig's description of the atmospheric moment that is possible in a tactile experience. "There comes a voluptuous moment when the senses and the whole skin tingle with a sharpened awareness of the body and the world around."[4]︎Images that show Atmosphere

Sound & Smell

We not only see a cityscape with our vision and touch, but we will also sense its tactile qualities through the sound of our feet on pavement, the echoing of cars and trams off of buildings nearby, the smell of the wet pavement or the heat radiating off of a dark-painted wall. These tactile sensations give us far more information than we acknowledge. Non-visual sensed impressions were critical in my experience of the space, although they are not evident in the photographed images. (They are more apparent in the video and written narratives). From my subjective point of view, some images captured the sensations or atmosphere that I was feeling.

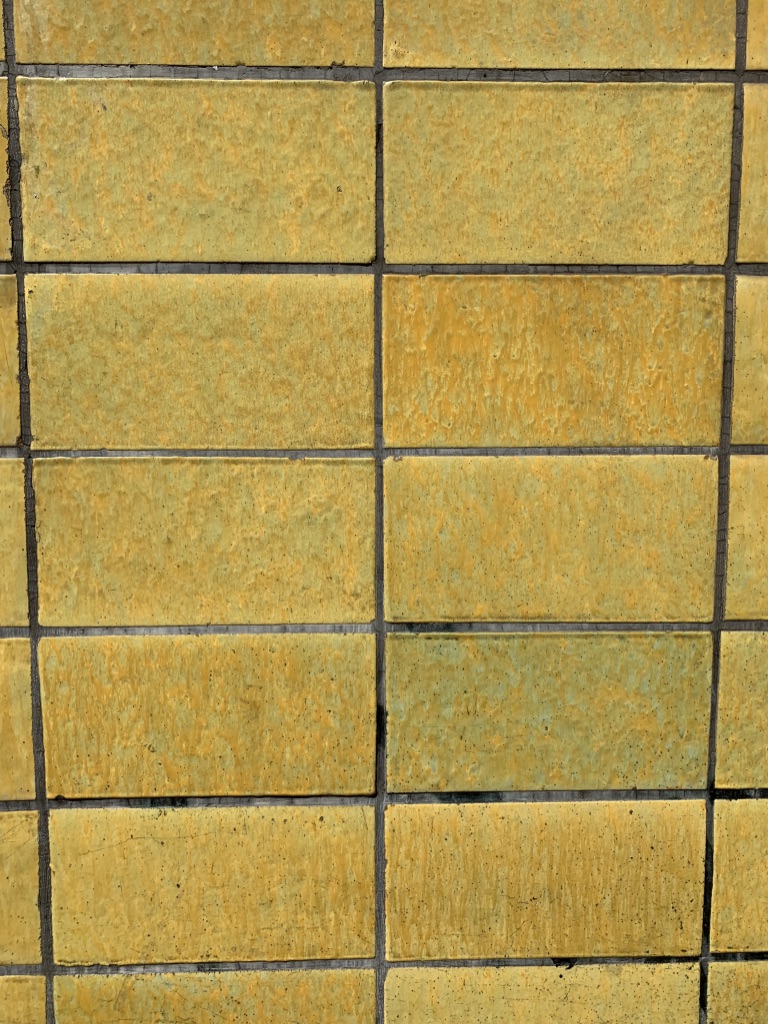

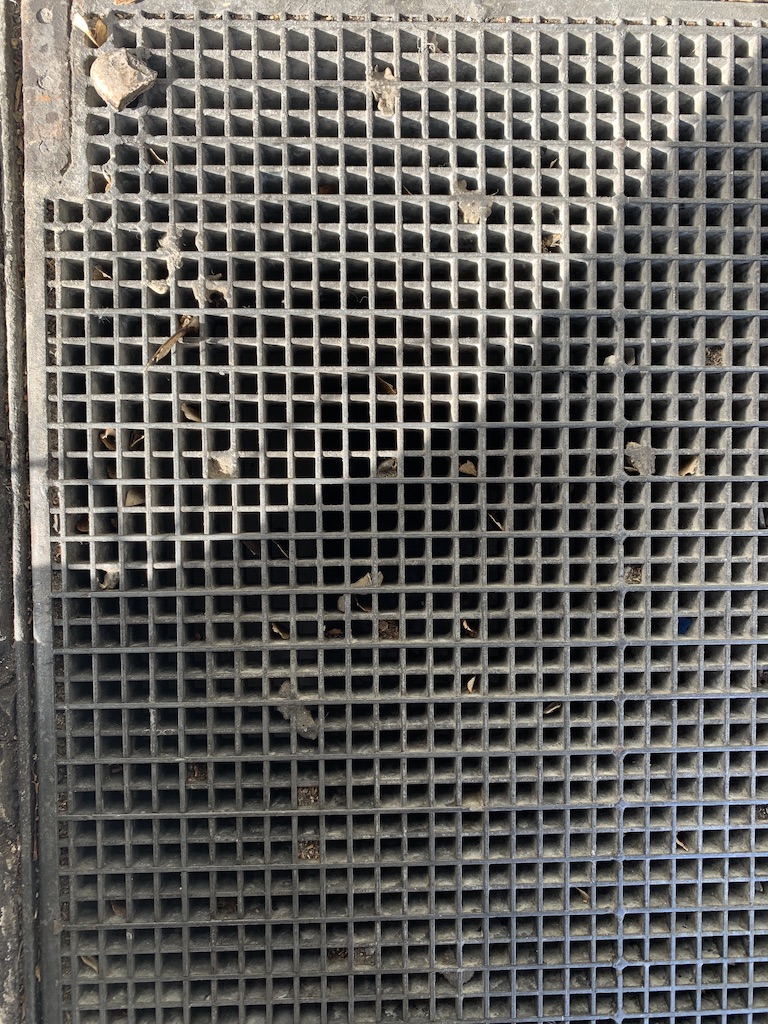

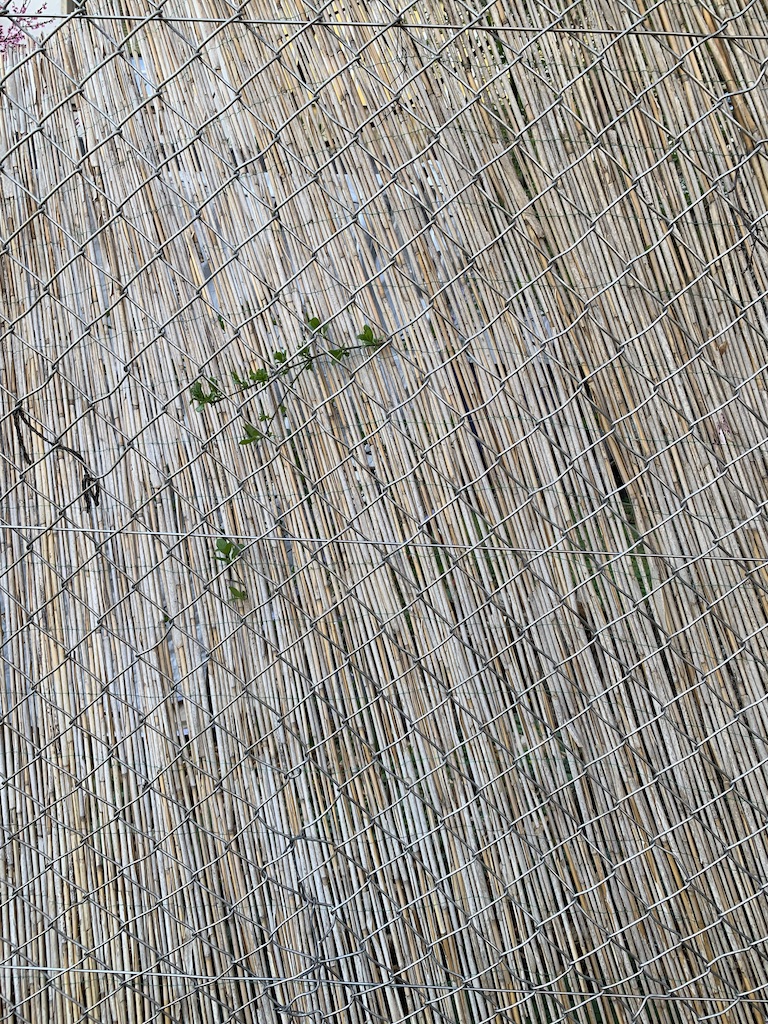

Texture

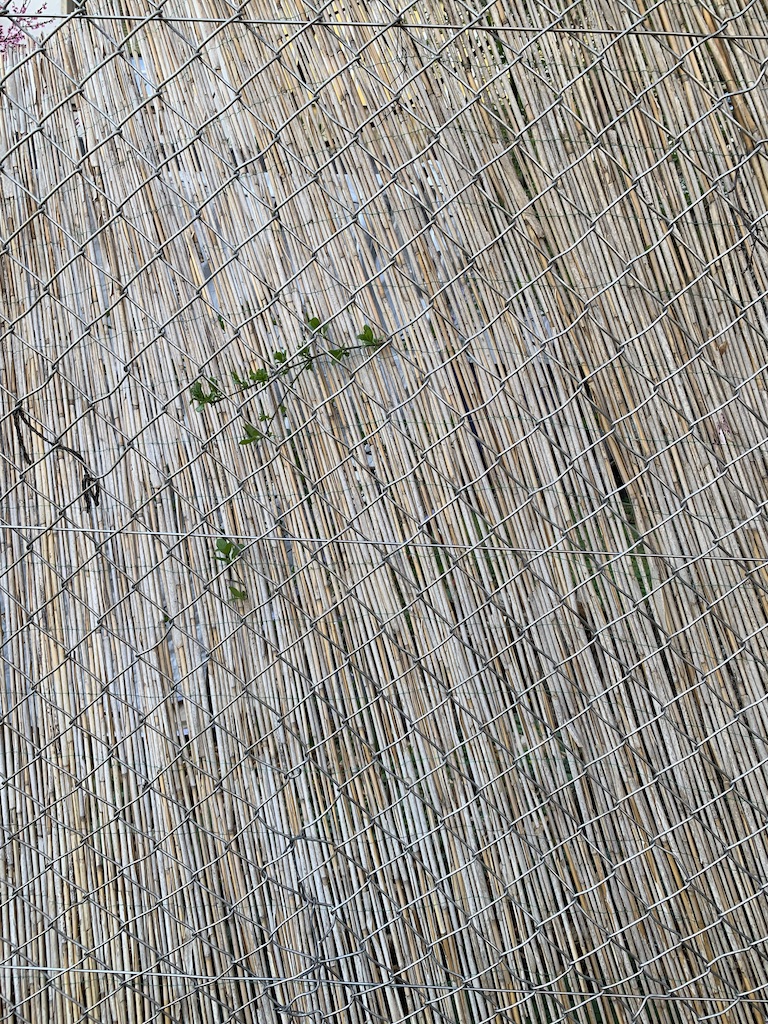

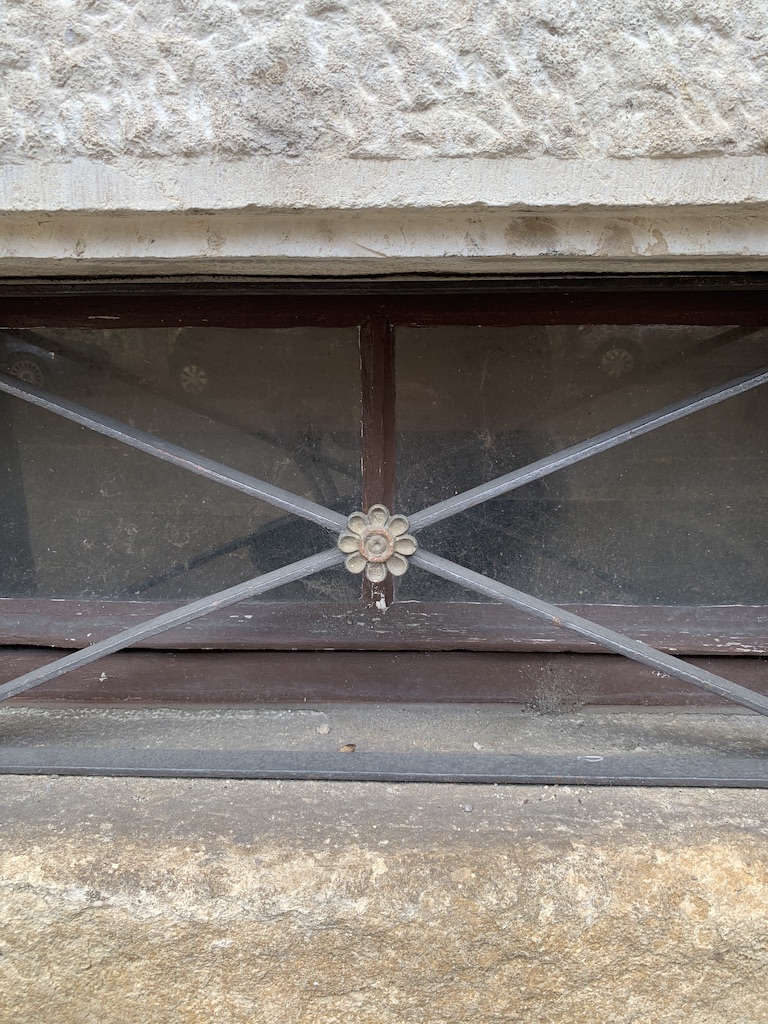

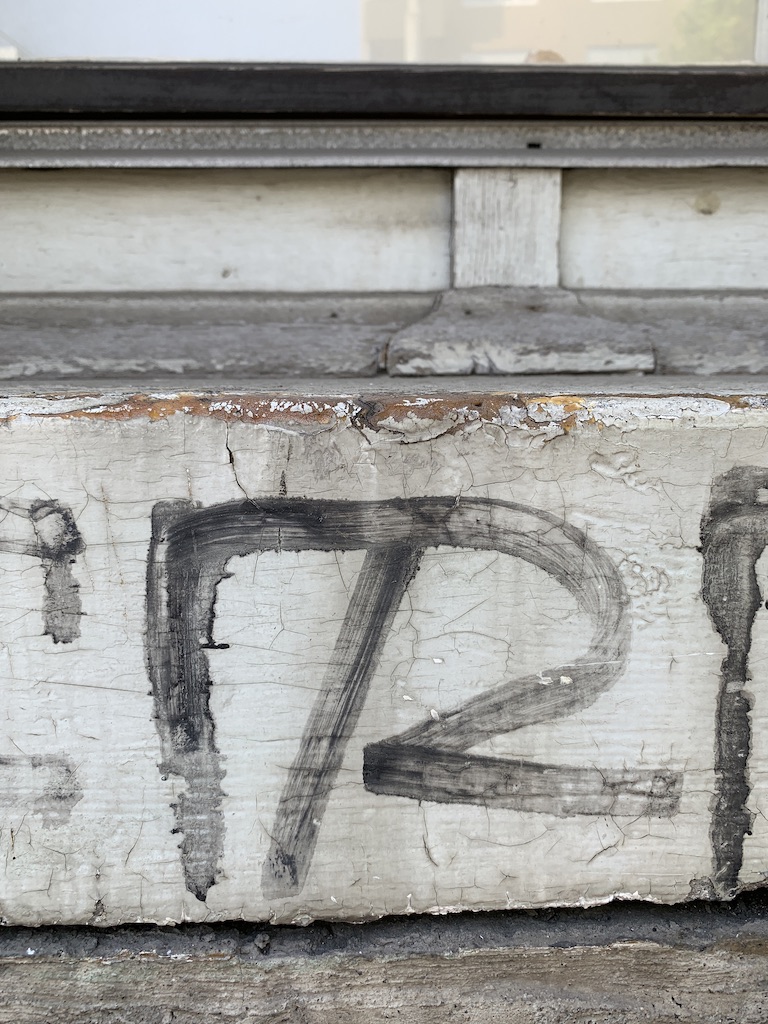

Considering the image of this passage, we can also understand that we see in a tactile manner. We 'see' the coolness of a dark passageway from street to private space and sense it even before we arrive, the mood or atmosphere already being created in our mind. In this same way, we may also see and can visualize texture even before the touch. A photo of my feet on the ribbed concrete,shows the textural surface of the ground, and without physically touching it is possible to understand the way it would feel if you run your foot over it. This seeing of tactile qualities is referred to as synesthetic correspondences, the intertwining of vision and tactility. Madalina Diaconu discusses this concept in her essay: Matter, Movement, Memory, referring to Merleau-Ponty's idea of vision as "a contact over distance" and as a "palpitation" with the eyes, further stating: "The pedestrian, too, "palpates" the surface of buildings, feeling their size. Shape and firmness, protrusions and edges."[5]︎Images that show Texture

These textural impressions are essential in allowing us to understand the structures and surfaces around us and many of my photographic images focused on this very tactile aspect of the urban space. Juhani Palassma reflected on the importance of texture in architecture: "Buildings should be pleasant to touch… Texture is the means to achieve the right tactility, not just to the touch but to the eye as well."[6] It is a reminder that the surfaces we encounter in our urban space invite us to look closely, touching with our eyes and when possible our hands, feet and body.

Our bodies are not standing still in space, and so hand in hand with this tactility and physicality is the impact of time and movement on the experience. We are not just moving through the urban space we are immersed in it and each movement; however slight changes the experience or view.[7]During my walks, a step forward might bring me into a shadow and change the appearance of a surface, which moments earlier had been yellow, to brown or moving away from a busy street might allow me to hear birds where before there was only traffic.

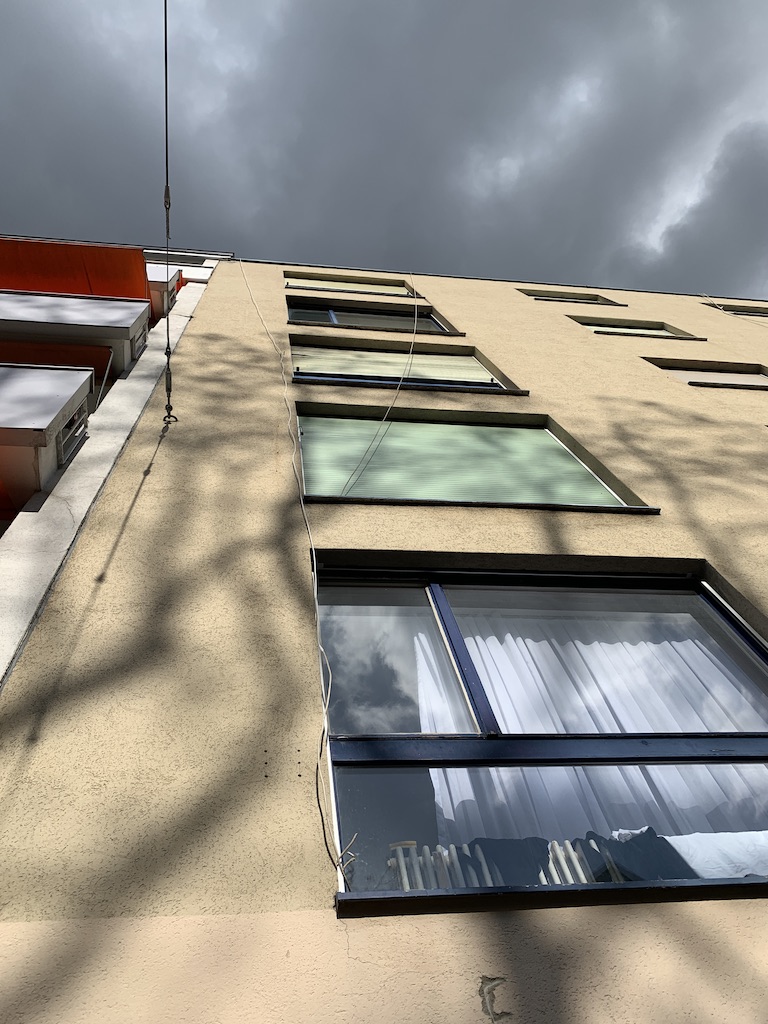

Freedom of Gaze

Physically moving through the space also allowed almost complete freedom of gaze, and the ability to move around the viewed object or scene to frame it in different manners. With each step, decisions could be made on how to proceed. Walking forward created time narratives as well, stories that had beginnings and endings. Illustrating this idea, figure 14, shows an image glimpsed from a mirror discarded in an entry passage of a building, a banal image but nonetheless an image which has a story of surprise at finding the mirror and then in moving to see my image and finally composing a new image. This image would not have been visible without being able to move my body into a non-public area, illustrating both freedom of gaze and time narration.︎Images that show Freedom of Gaze

Rhythm

This movement, through space and time, has not only an impact on the changing view it also established a rhythm and a pace. Sometimes the experience was slow as I stopped many times to write and think, and at other times, I quickened my pace to match those of my fellow walkers on the sidewalks. "Cities can be recognized by their pace just as people can by their walk"' wrote Musil. This "one great rhythmic throb," can hardly be measured, but only felt by immersing oneself in the city; therefore, it implies once more a metaphorical tactility”.[8] My impressions of rhythm were most apparent in the videos of my feet walking where I heard and felt the pace of my body. Moving on to a major street would bring the rhythm of trams and other walkers into the picture. In one sequence of images and videos, I captured the ceaseless rhythm of bikers returning from work around 5:30 pm – a constant whizzing by as I sat quietly in the center of the road.Repetition

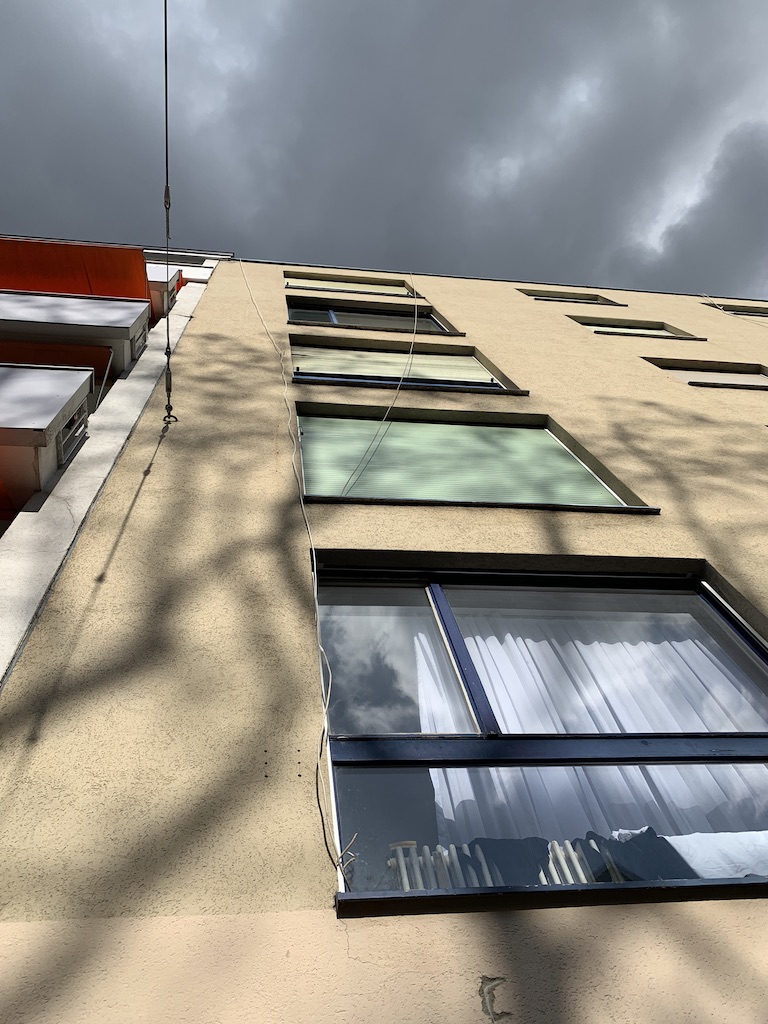

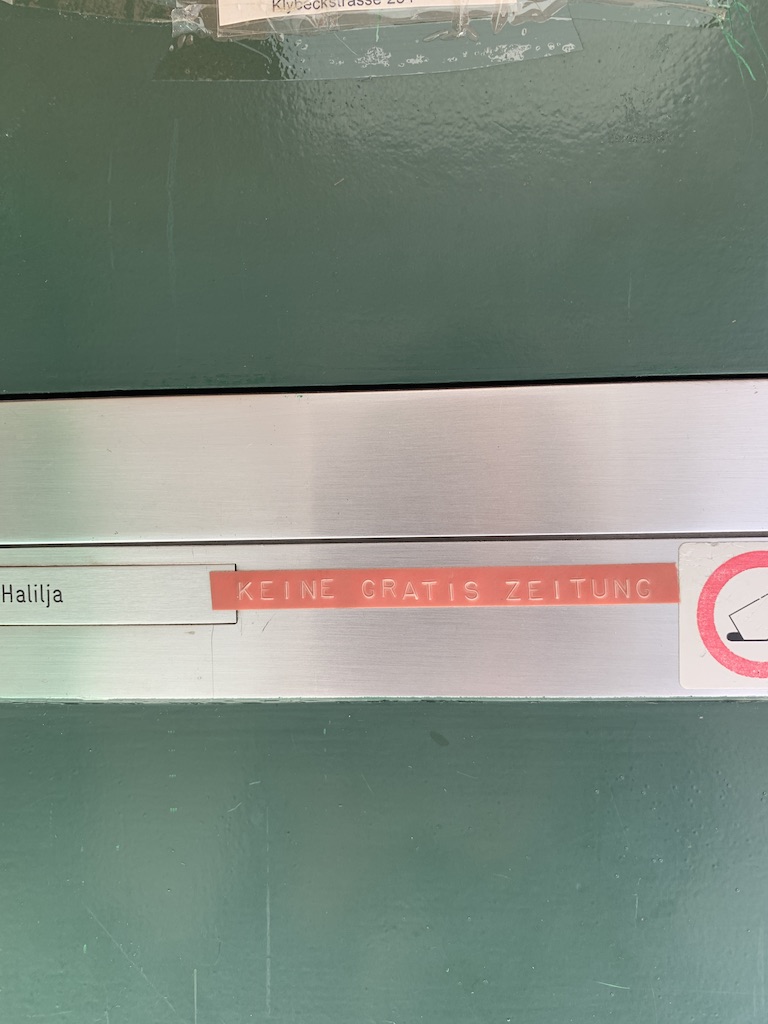

Repeating elements were also a constant part of the urban experience, whether seen at once or discovered over time through movement. This repetition became obvious the longer I explored Klybeck. Certain elements, which I had seen on one street, appeared again in a slightly different configuration a street over. For example, the cigarette machines, unremarked at first, reappeared over and over. The mailboxes repeated one after another down the street or the flower boxes and awnings creating patterns with their shadows. or a building which spanned an entire city block with the broad stripes of orange paint, each swath of color creating a repetition that defined the visual image of the street.︎Images that show Rhythm, Repetition and Pattern

Quality of Light

Even without moving the experience shifted with the passing time. The quality of light changed minute by minute even whensitting still on a bench. The reflections and absorptions of the light from buildings continuously changed the visual appearance and even the mood of the space. Juhani Palassmaa described this quality of light: "Light is the most subtle of the means of architecture; it can express joy and happiness, as well as melancholy and sorrow. We do not "see" light directly, and architecture somehow "materializes" light through reflecting surfaces, in order to bring light to our attention. James Turrell speaks of "tactile light" and "the thingness of light."[9] Here Palassmaa is speaking of the ability of the space to show the qualities of light. I took photos which attempted to capture this quality of light but often the effect of the light is changed and muted through the lens of the camera, and it is only when considering the image alongside the memory or the narration do the full qualities become evident.

︎Images that show Quality of Light

Shadow

Alongside light, there are, of course, shadows. Shadows within the urban space define not only the physical edges and protrusions of objects and buildings but also the experience of time. A shadow will move up a wall and turn a corner in a matter of minutes; they change as we move forwards or backwards even slightly. The shadows of trees move gently with the wind over the buildings, and ever-present is my shadow as I move through the space giving an indication of my bodily presence and situation in the space.︎Images that show Shadow

[1] Pallasmaa, 2009 p.116

[2] Diaconu, 2011 p.24

[3] Amundsen, 2018 p.2

[4](Widely cited quote by Anton Ehrenzeig from his introduction to Maurice de Sausmarez's book on the artist Bridget Riley.)

[5] Diaconu, 2011 p.16

[6] Paetzold, 2011 p.29

[7] Tuan, 2001 p. 390

[8] Paetzold, 2011 p.26, Here quoting the Austrian Philosophical writer Robert Musil.

[9] Amundsen, 2018 p.3

Details, Layering and Memory

UNEXPECTED | UNPLANNED | HUMAN PRESENCE AND PERSONALIZATION | REFLECTION |

MEMORY

At every instant, there is more than the eye can see, more than

the ear can hear, a setting or a view waiting to be explored. Nothing is

experienced by itself, but always in relation to its surroundings, the

sequences of events leading up to it, the memory of past experiences.”[1]

– Kevin Lynch

Within the space, we begin to notice details which help to paint a picture of the space. These details create a rich dialogue about the space if they are noticed, but naturally, there is a tendency to stop noticing the details of our space through the habits of our everyday life. Alain de Botton[2] reflects on this; "Home, on the other hand, finds us more settled in our expectations. We feel assured that we have discovered everything interesting about a neighbourhood, primarily by having lived there a long time."[3] By taking the view of the traveler and seeing everything anew we can begin to notice overlooked details, de Botton continues; "We approach new places with humility. We carry with us no rigid ideas about what is interesting." We are receptive to noticing the details, and this is part of the experience of urban space.”[4]

Unexpected

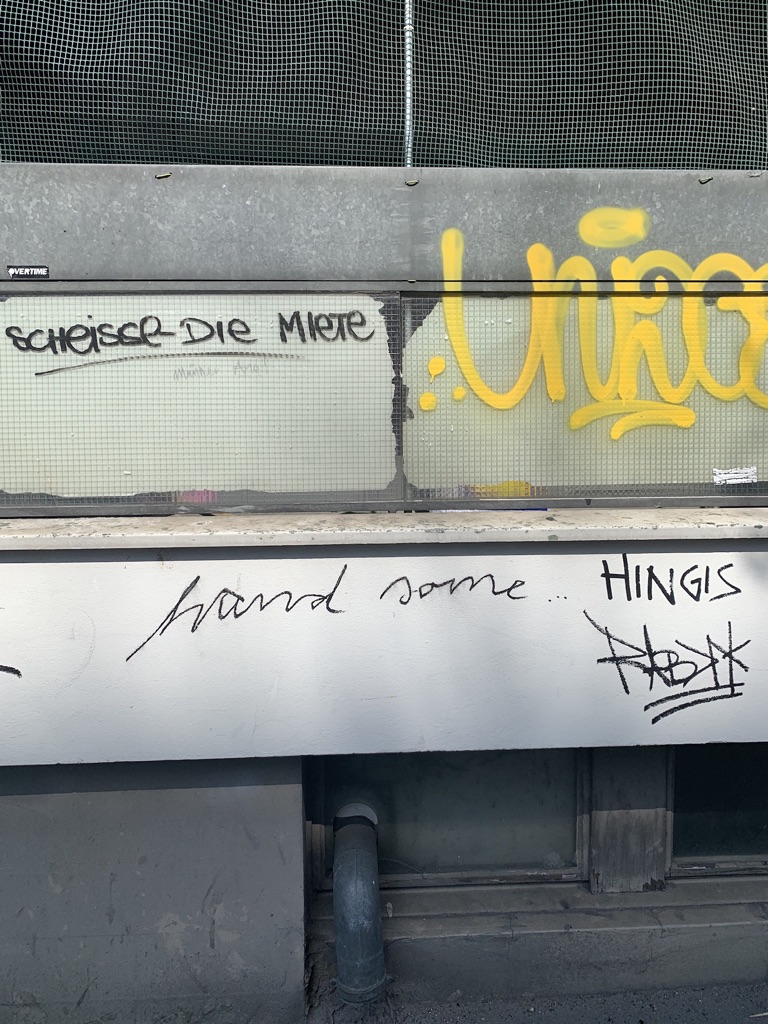

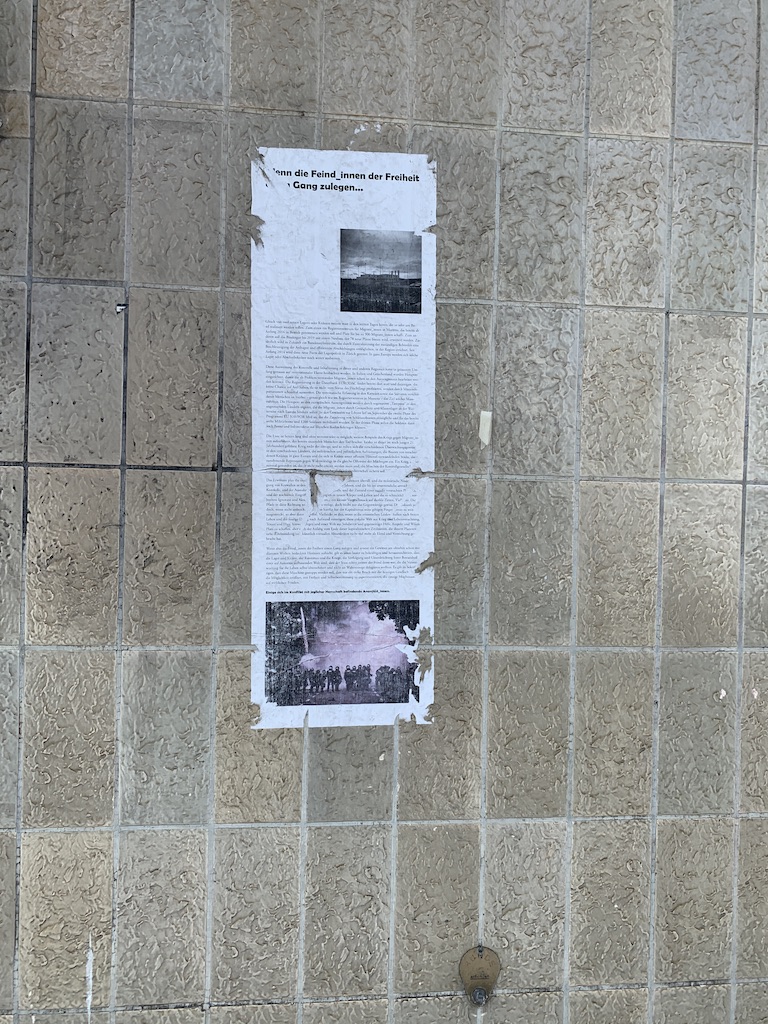

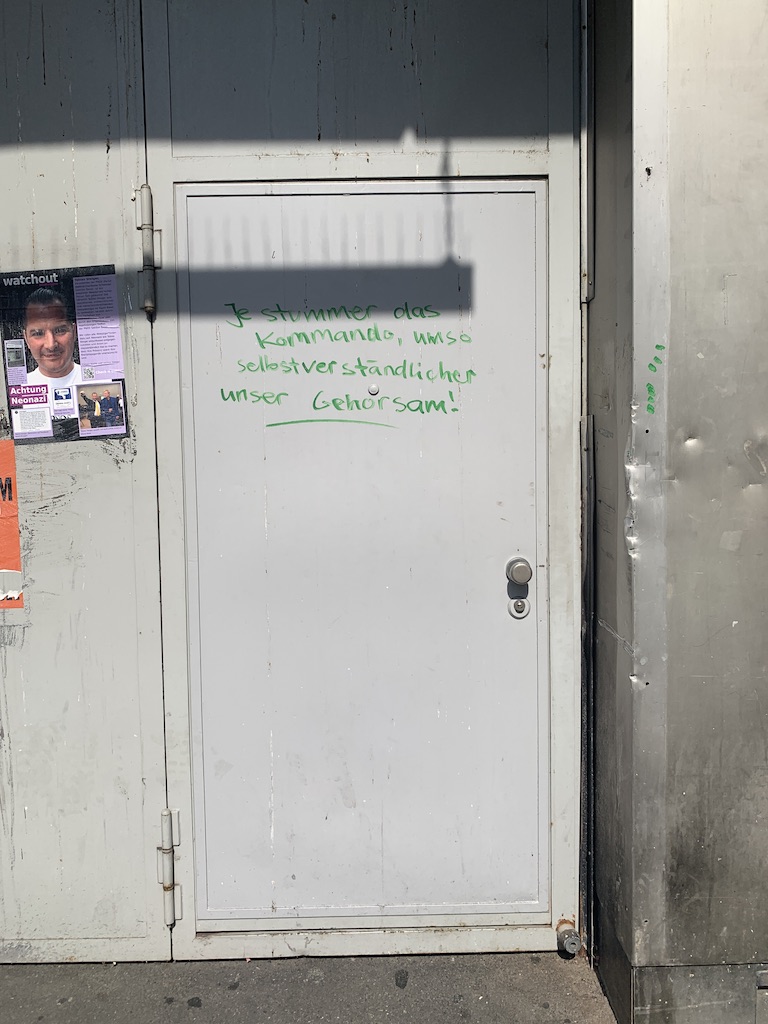

One characteristic of the experience of the urban space is the unexpected. This is something that also was revealed during the workshop when many of the participants remarked that being wholly free and directed to look closely allowed them to discover many unexpected things that they would not typically have experienced. Many of these unexpected things are a juxtaposition of images that only occur because of the situation of being in the space, a certain surprise realized by looking closely. Figure 19 shows the beauty of a simple empty postcard holder against a tiled wall, many of these unexpected elements appear by observing the mundane details.Unplanned

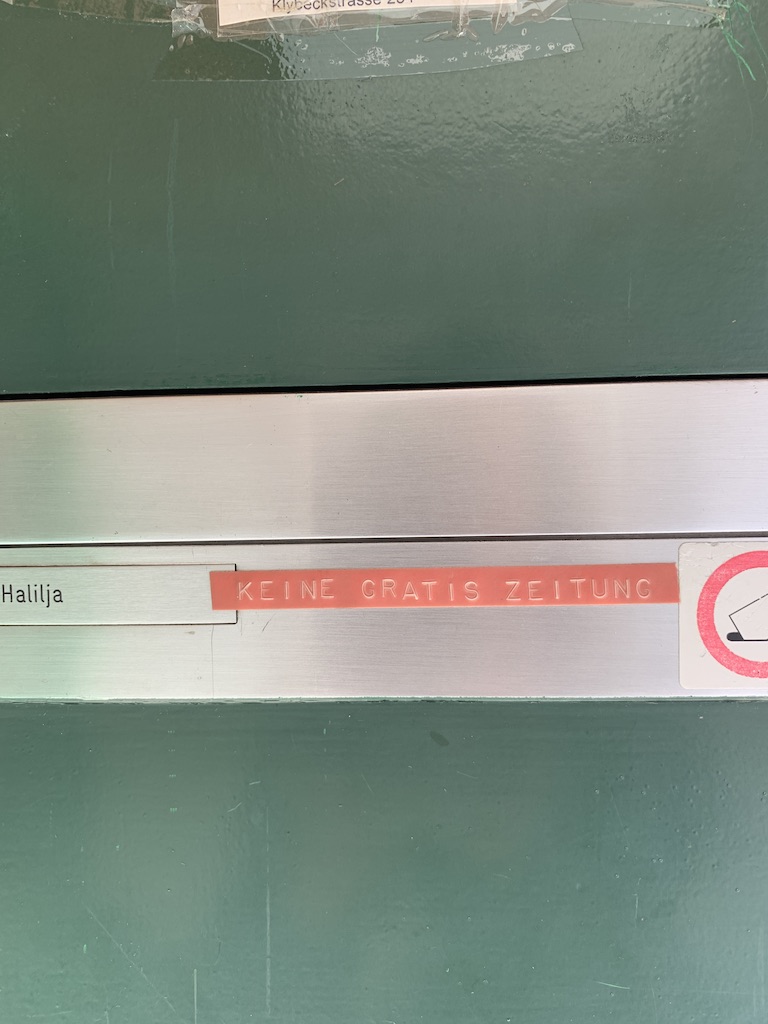

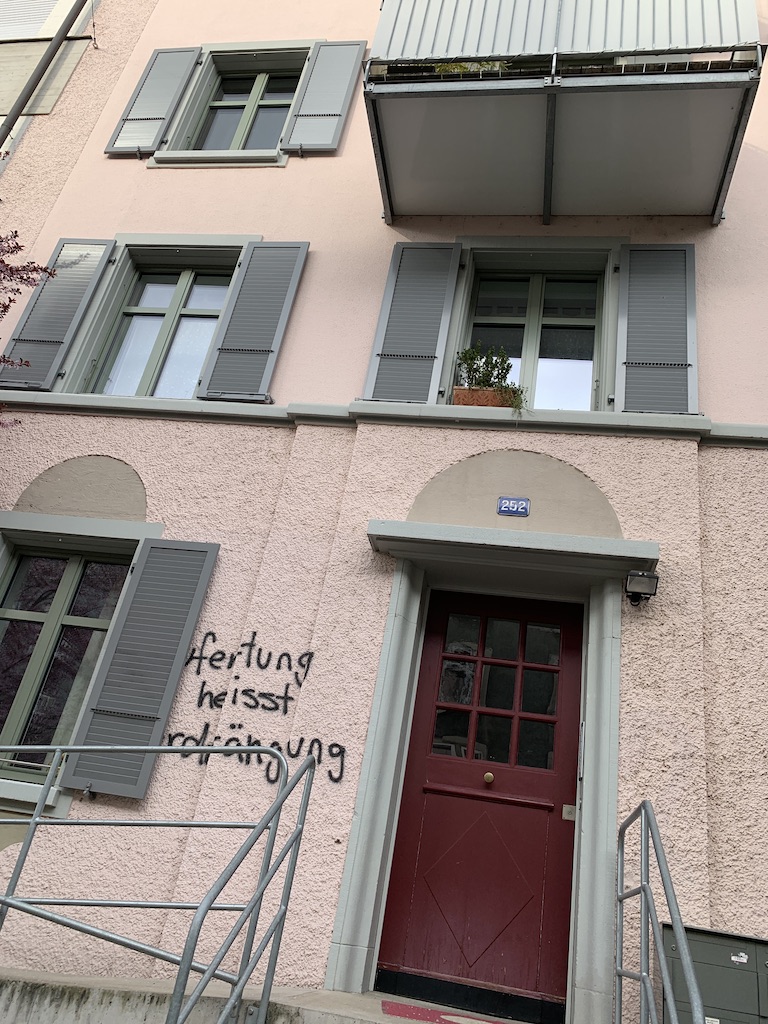

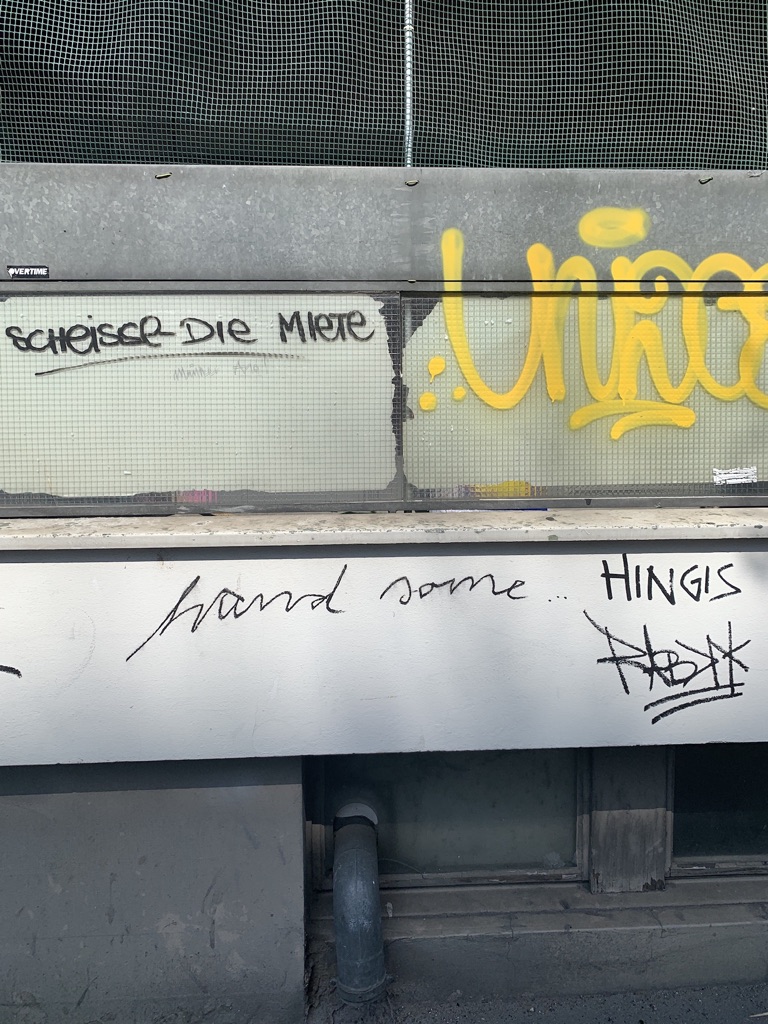

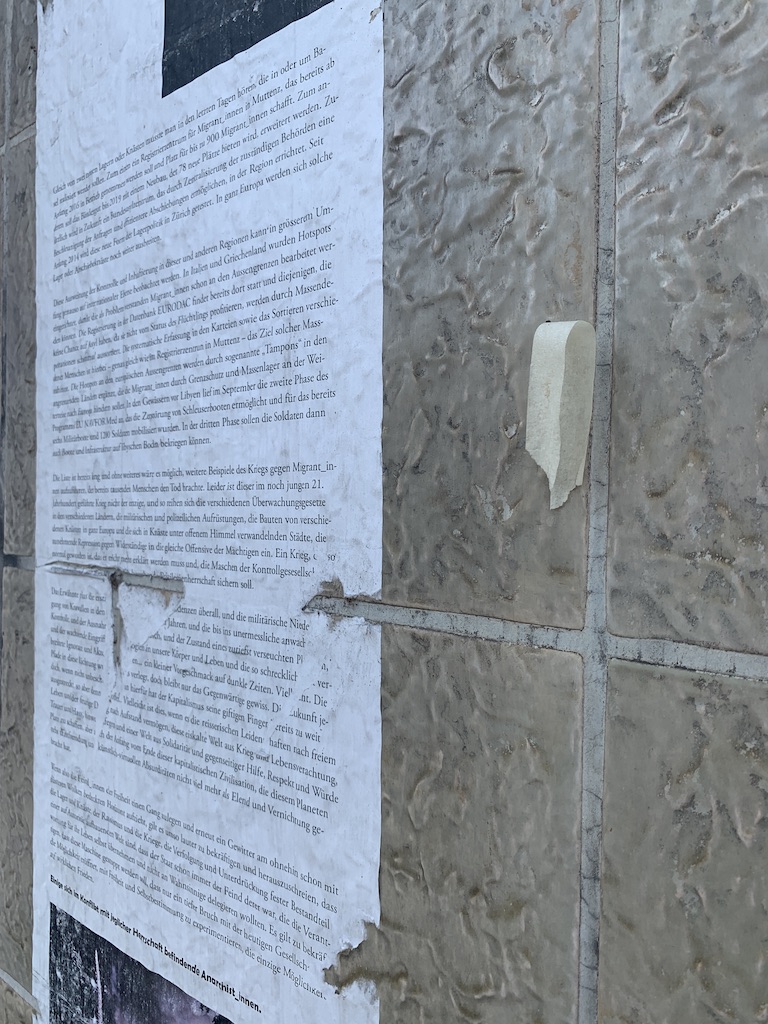

Another characteristic of the space, which exists alongside the unexpected is that of the unplanned. The unplanned elements are parts of the urban space that exist but were not designed to be in that particular way, no urban planner would think to create the space in that manner. Some examples of this would be the juxtaposition of unusual architectural styles one beside the other or clashing paint colors on neighboring buildings, (fig.20,) or the growth of wild plant material taking over a light pole and curb, (fig 21 & 22). These unplanned elements create a visual sense of uniqueness and reveal the chaotic built-over-time nature of urban space.Human Presence and Personalization

These unplanned and un-expected elements often reveal another category of the detailed and layered urban space, that of human pre-sence. My photos generally showed limited human presence as I did not pur-posefully seek to photograph inhabitants of the space. Despite this, I saw traces of human presence in many of my images and believe that this is something that is understood and sensed by those who dwell in the urban space. Within this category of human presence as well, we can speak of personalization. Images of human presence for me were when the everyday life spilled out into the public space or when the urban dwellers left their marks on the space. For example, figure 23 shows a religious symbol installed within the public area, illustrating human presence. Figure 24 shows a collection of unusual items collected in front of someone's garage.Reflection

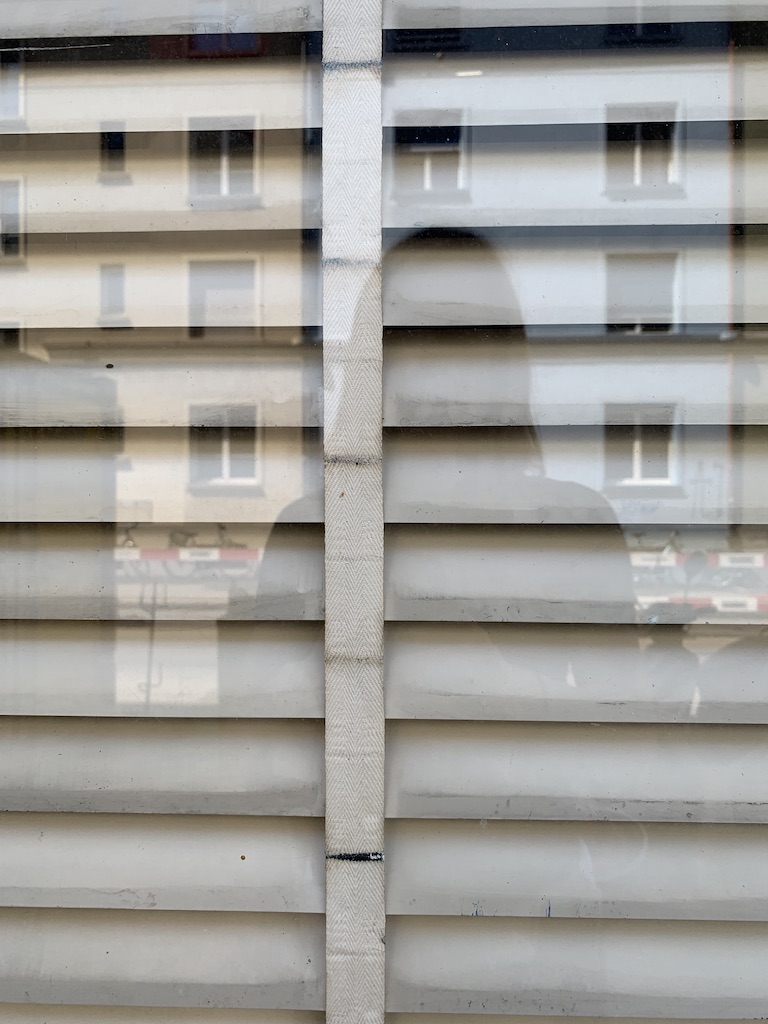

Looking through my images though there was one constant, on every walk and every day, no matter what path I took I was confronted with my reflection and the reflection of the buildings and sky around me. The urban space was reflected and amplified in the cars parked on the street, in the bus stopsand commercial store windows. (fig.25) These reflections expanded and multiplied the space, providing glimpses of what is behind or above, while eyes remain fixed forward. Often the reflection distorts the space and so created other realities of the experience of urban space. In a very interesting way seeing my reflections while immersed in the space placed my perceived image into the perceived image of the space.

Memory

Finally, layering over all of these perceived images in the space are memories and images in the mind. These memories are not visible in my photography and perhaps not often in the narratives either, but I was often aware of them. Finding a building on the street that I had glimpsed from the tram a day or two before layered a memory over the new experience. Coming across a hop-scotch game drawn in the sidewalk, I remembered my small-town chalk games and layered those mental images into my experience of Klybeck. Often, I would recall the image of the street seen earlier on google maps as I walked down a street anticipating my next turn. These mental images and memories are ever-present in our experience of urban space.[1] Lynch, 2005 p.1

[2]Alain de Botton is a Swiss-born British philosopher whose books emphasis philosophy’s place in everyday life.

[3] de Botton, 2002 p.246

[4]De Botton, 2002 p.246

Virtual and Unreal

GRAVITY FREE | UNREAL | OPEN | CURATED |

DECEPTIVE

“Public and private have been nearly inverted by digital media, iPhones and streets wrapped in computer screens. Clearly, we can barely remember what we used to call urban life - even just fifty years ago.”[1]

–Norman M. Klein

There is another version of urban space that exists in the online world. This space has characteristics distinct from the lived physical experience. In this space, we can float above the street and fly across the sky. We can view the whole neighbourhood at once or zoom in close and inspect a small detail as the building dissolves before our eyes. We explore this space without sound, smell or touch.

Gravity Free

This ability to be gravity-free allows a view of the space which was until recently only possible by building high towers or using flying devices. Now, any citizen can examine their space from far above. They can look into what was once restricted private courtyards, hovering above them, and seeing how the space is divided up between the buildings, even looking into what are normally private courtyards not visible from the street. They can walk down the streets of their neighbourhood floating five meters in the air, as I am doing in figure 26. This elevated view gives a unique impression of the space that is impossible to have in reality, which bring us to the next characteristic of the experience of virtual urban space; it is unreal.Unreal

Urban space as experienced online, on Google Earth, always has a strange unrealness to it. Even when it seems that you are experiencing it as virtually real, at street level, turning and looking 360 degrees, there are always unreal moments. First and foremost, the street names are continually appearing in the space as well as helpful arrows inviting you to move forward, backwards up or down. During my virtual walks, there was a never-ending stream of strange occurrences, at times the leaves were dead on the trees, and a few meters later they are green again, or a building under construction is complete a few meters further down the road. All of the faces encountered are strangely blurred, although they seem to be looking at the viewer. If you zoom in closely, you will see the google trademark emblazoned on buildings and in the sky. Overhead wires do not connect; bikes melt into the street; we can see more faceless people from open windows the sky disappearing above them.Further adding to the unrealness of the online space is the complete silence of the experience, which is in marked contrast to lived urban space. Interestingly, Baudrillard referred to this lack of sound as one of "the most precious qualities of photography: its silence. Whatever the violence, speed or noise that surrounds the real object, its instant image gives back to the object its immobility and its silence."[2]This strange, silent online space is not the real Klybeck as experienced in a tactile, bodily manner; this is not a space that could ever exist in the physical world.

Open

This space is also open; the access is available to anyone with an internet connection whether you are near or far. You may walk these streets, inspect the restaurants and gaze at the sky whether you are in Klybeck or on the other side of the world. The urban space online is available to all and anyone can also add to the knowledge of this space through the uploading of their person-al panoramic images to google maps or by geotagging their photos, writing restaurant reviews with photos or sharing impressions of the space on social media. Much as in the physical space, there is some personalization possible through the selection of image material tagged and uploaded.Curated

At the same time that this space is open, it is also curated, with many of the images tailored to the purpose of the platform. Instagram images have a distinct look and focus; sometimes, they are commercial at other times showing 'Instagram friendly' facades, touristic images and yoga. (Fig.27)The Google maps images are generated by google technology and the occasional private contributions by sanctioned users. The other online private images such as geotagged images are uploaded by private citizens and are usually concerning a commercial enterprise or a beautiful or visually appealing image. In this way, the image of Klybeck is not that of everyday life, but rather a curated view, provided by others to the virtual viewer.Deceptive

This leads to the obvious problem with a space that can only be explored through the eyes of others and that is that the experience is deceptive. Looking at the online images after having thoroughly explored the space in a physically and visually engaging way, it became evident that many of the images encountered were not showing what was there. Sometimes they were entirely off as in the geotagged images, likely gathered by the cruise ship tourists parked in the area, which showed the Basel Munster, which is located in the historc old town, as being located within my research area. There were also less obvious distortions such as a large number of images of the Holzpark which appear during an Instagram search, giving the impression that this is the prevalent aesthetic feel of Klybeck when in reality it was just the most photographed for social reasons.It would be easy at this point to make an argument for the superiority of one experience over the other, the lived or the virtual, but that is not my intention in this thesis. I am interested in all aspects of the urban space as the visualization of the space requires a complete understanding of all of the characteristics which make up the experience of urban space and for much of the population that experience now includes a visit to the online space.

[1] Noever & Meyer, 2010 p.44 (From Norman M. Klein, the American urban and media historian’s manifesto: What if and what next?)

[2] Moya Pellitero, A.M., 2007 p.96